Game Architecture Using Scriptable Objects Part 2

In my last post I introduced the scriptable library, it’s inspiration and my motivation for creating it. This time we’re going to go further into the code and outline some of its the more interesting aspects. I will not really go too deep into when and where to use it as Ryan has already done a pretty good job.

Variables

A “scriptable” variable is an object that represents a single value. That’s… basically it. It can be a player’s health, a user’s input or any other value that you might want to “inject” into a script. The cool thing about this is that it is essentially a shared state between multiple elements in your game. Also, it is easily accessible in the project and it’s value can be set directly from the editor, which means it makes things very easy to test.

public class Variable<T> : ScriptableObject

{

public T value { get => realValue; set => realValue = value; }

[System.NonSerialized] private T realValue;

[SerializeField] private T _value;

private void OnEnable()

{

this.hideFlags = HideFlags.DontUnloadUnusedAsset;

realValue = _value;

}

private void OnValidate()

{

realValue = _value;

}

If you’ve watched the lecture you may notice two key differences from the original code.

First it’s HideFlags.DontUnloadUnusedAsset. HideFlags is very misleading name, because it’s way more than “flags for hiding”, but I guess HideUnloadAndSaveFlags was deemed too long. For us, what is important is that we can use it for force Unity to keep the current instance of our variable around. Otherwise, even if the same variable is referenced in the next scene, the current instance is going to be destroyed (especially if you call UnloadUnusedAssets) and then a new one will be created in it’s place - which is rarely something you need.

You may have also noticed that we have a realValue in addition to the _value. What’s up with that?

Well that gives us the benefits of having a serialized value, that we can access and set in the inspector, combined with the benefits of not having to reset this value manually back to the original after some script changed it in play mode. Basically we’re having our _cake and eating our _realCake, too. I crack myself up.

OnValidate does two things here:

- Ensures, that

realValueis set to_valueevery time we change_valuethrough the inspector. - Resets the value of

realValueto_value, after the asset has been deserialized, which happens, most importantly, after domain reload.

You probably also noticed the [System.NonSerialized], which might seem redundant. After all we all Unity doesn’t serialize private variables, right? Right? Uhm… about that:

Unlike other cases of serialization, Unity serializes private fields by default when reloading, even if they don’t have the SerializeField attribute.

There you go - straight from the horse’s… documentation. While this serialization might not create a specific problem, I generally advise forcing your private variables to [System.NonSerialized] in ScriptableObjects, to prevent any hidden/unwanted behaviour.

That pretty much covers it - so little code, so much explanation.

References

Very often, when working with scriptable variables, you will run into the problem of not being able to decide if it’s better to use one or leave a field as a local parameter. While I could give you some esoteric pointers and rules of thumbs, our friend Ryan Hipple has given us something better - code! Which I have improved a bit.

[System.Serializable]

public class VariableReference<T>

{

[SerializeField] private bool _useConstant;

[SerializeField] private T _constant;

[SerializeField] private Variable<T> _variable;

public T value

{

get => _useConstant ? _constant : _variable.value;

set

{

if (_useConstant)

{

_constant = value;

}

else

{

_variable.value = value;

}

}

}

}

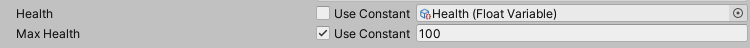

So, what this class does, is that it gives you the ability to set both a scriptable variable and a regular local parameter and cycle between the two as needed. You can also just set a parameter and add a scriptable variable later if you need one. You don’t need to subclass or implement nothing, because Unity has been able so serialize generics for a while now. Something like this:

public VariableReference<float> _health;

will take FloatVariable as a parameter. And, thanks to some editor “magic” in the inspector the whole thing looks like this:

Events

Events, on the other hand, are pretty straightforward. It’s just a script with an event and a two methods to encapsulate the event. The encapsulation we need in case we decide to store the callbacks in some different manner down the road.

public abstract class TypedEvent<T> : ScriptableObject

{

private event System.Action<T> _action;

public void AddListener(System.Action<T> listener)

{

_action += listener;

}

public void RemoveListener(System.Action<T> listener)

{

_action -= listener;

}

public void Invoke(T arg)

{

_action?.Invoke(arg);

}

}

You’ll notice, that this is a Typed event. Each event has a payload type, that gets delivered to the listeners. There is also a VoidEvent, but it’s really not that interesting. These events live as files in the project and you can subscribe to them directly by passing them to a script in the scene or use a responder. Responders are useful if you want to try (and key word here is always “try”) to separate the library from the code of your game as much as possible. Whenever the events gets invoked the responder passes this invocation to a corresponding public method through a UnityEvent.

public abstract class TypedEventResponder<T, E> : MonoBehaviour where E : TypedEvent<T>

{

[SerializeField] private E _event;

[SerializeField] private UnityEvent<T> _response;

private void Awake()

{

_event.AddListener(OnEventRaised);

}

private void OnDestroy()

{

_event.RemoveListener(OnEventRaised);

}

public virtual void OnEventRaised(T payload)

{

_response.Invoke(payload);

}

}

For each type of event you can subclass TypedEventResponder to create it’s corresponding type of responder. Like this:

public class IntEvent : TypedEvent<int> { }

public class IntEventResponder : TypedEventResponder<int, IntEvent> { }

The major downside of he scriptable event system is that you can only pass a single argument. However, you can get around that by creating your own container class to hold your arguments.

[Serializable]

public class Container

{

public float health;

public string message;

}

public class MyEvent : TypedEvent<Container> { }

public class MyEventResponder : TypedEventResponder<Container, MyEvent> { }

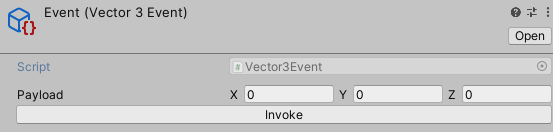

The last major feature of events I want to show you is the ability to invoke them manually. This is something I find very cool and useful and it helps reduce development time by not having you try and invoke the event through the game and hope it works. In the editor it looks like this:

Currently, the manual invoke is supported for handful of types, however I hope that soon I’ll be able to provide editor code for using it with custom container classes, like the one above.

RuntimeSets

Runtime sets are a very simple concept, that can help replace a number of other ways we do things in Unity. First of all, a RuntimeSet is simply a scriptable object that holds references to “things” in the scene. These “things” can be GameObjects, Components, or other type of UnityEngine.Object derivatives. What this does, is it provides you with another way of dealing with groups of objects, which might be superior to existing ones.

- It’s immune to initialization race conditions, unlike singletons.

- It’s not performance intensive like

FindObjectOfType - It’s less error prone than Tags. And you can a single object in multiple lists, where as you can only have a single tag for object.

All you need to do to use RuntimeSets is to subclass the script with the same name and implement it for the type you need.

public class RuntimeSet<T> : RuntimeSetBase, IEnumerable<T>

{

[System.NonSerialized] private readonly HashSet<T> _values = new();

public void Add(T value)

{

_values.Add(value);

}

public void Remove(T value)

{

_values.Remove(value);

}

...

As with other concepts in this library, RuntimeSet<T> comes with a corresponding in-scene script (mostly for convenience):

public class SetRegistar<T> : SetRegistarBase<T>

{

[SerializeField] private T _toRegister;

protected override T _object { get => _toRegister; }

}

public abstract class SetRegistarBase<T> : MonoBehaviour

{

[SerializeField] private RuntimeSet<T> _set;

protected abstract T _object { get; }

private void OnEnable()

{

_set.Add(_object);

}

private void OnDisable()

{

_set.Remove(_object);

}

}

You can subclass SetRegistar<T> to have your objects be registered automatically when enabled.

Side note: I am totally not jazzed about RegistAr, however I couldn’t find anything better for “something that registers things”. Suggestions are welcome.

Finally

I hope that this overview was useful and shed some light on how the scriptable library works. I will probably update it with more stuff in the future, so stay tuned. I also hope that can you this code in your next project, or get inspired to use a similar approach. Happy Coding!