Crafting an interpreter

If you are anything like me then you probably talk to computers. Sometimes for a living, sometimes — for fun. The premiere way of communicating with these weird machines, and getting them to do stuff, is through programming languages. And oh boy do we have a lot of those! Low-level, high-level, functional, object-oriented, procedural and just plain weird.

Motivation

Yet, very rarely do we think about how writing words in these weird languages makes the computer move bytes from the memory to the CPU and back again. I mean - we all know that the parser parses, the compiler… um, compiles, but there is also an interpreter, and a translator, but aren’t these all the same thing? And C++ has a linker, what’s up with that? Do other languages have linkers?

To answer all of these questions (maybe not about the linkers, that’s a whole different story), and many more I took up the task of building my own little interpreter/translator/compiler/whatchamacallit from scratch.

I was helped along the way by a little book called Crafting Interpreters by Bob Nystrom, both of which I highly recommend. I’m going to try and not repeat things, that Bob has already written in the book, but share my own key takeaways from the experience. For the purposes of the book Bob has kindly created his own language called Lox. It is a pretty generic high level language with some nice features, that are mostly there to have you implement them.

class A {

method() {

print "A method";

}

}

class B < A {

method() {

print "B method";

}

test() {

super.method();

}

}

Theory

Languages are all about grammar. And in the case of a programming language we have not one but two whole grammars. One for the words - a lexical grammar, and one for the expressions - an expression grammar. But what is a grammar?

Grammar Yahtzee

In the abstract a grammar is a set of rules, that describes a language. We cannot possibly describe all possible “strings” that are valid within a language, but we can describe a set of rules, that when followed would yield a valid string/sentence/word of that language. That’s why they are called production rules, and we can generate any string of our language, by playing these rules like a game. Bellow is an example of some rules for generating the language of breakfast.

breakfast → protein ( "with" breakfast "on the side" )?

| bread ;

protein → "really"+ "crispy" "bacon"

| "sausage"

| ( "scrambled" | "poached" | "fried" ) "eggs" ;

bread → "toast" | "biscuits" | "English muffin" ;

Lexical Grammar

The production rules of a lexical grammar govern whether a certain string is a valid element of the language - a keyword, an identifier or some mathematical operation. These languages are simple enough to be regular - ones, that can be covered with a regular expression, or a simple finite automata.

Initially, our “code” is just one big heap of text, from which of have to make some sense. To do that, we continuously try to apply the rules of our lexical grammar on every character of this text in the hopes that one them actually fits. You can think of these rules as moulds, that fit certain shapes. As soon as we find the right mould that fits the shape of “24.3”, for instance, we designate that piece of text as a number.

The process of making sense of the text and adding semantic meaning to it is called scanning. For every correct word of the lexical grammar, scanning produces a combination of its type, its value (literal) and the original text (the lexemme). That is called a token and is going to be the building block of our program.

public struct Token

{

public readonly TokenType TokenType; // TokenType.NUMBER

public readonly string Lexeme; // "24.3"

public object Literal; // 24.3 (the actual number)

}

Expression Grammar

Now, that we have our initial code nicely chopped up into tokens, it’s time figure out what these tokens actually do. To be able to do this, we will have to take a step higher, to the more abstract world of context free grammars. The rules of a context free grammar are more complex and allow it to define a more sophisticated language.

The production rules of an expression grammar, as the name suggests, allow us to put together the tokens we just created into expressions. By “playing”, the rules of the grammar we can generate an infinite set of valid expressions. For instance, the below grammar is a simplistic way of generating arithmetic expressions (it doesn’t take into account associativity and precedence, which are a whole different can of worms). By following its production rules, we can generate expressions like 2 + 2, 6 * (24 - 12) / 3.

expression → number | grouping | binary

grouping → "(" expression ")"

binary → expression operator expression

operator → "+" | "-" | "*" | "/"

However, we are more interested, playing the game in reverse. Given the expression 2 + 3 can we be sure it’s part of the grammar. Here’s a way we could have generated:

- Starting at expression, pick binary.

- For the left-hand expression, pick number, and use 2.

- For the operator, pick “+”.

- For the right-hand, pick number again, and use 3.

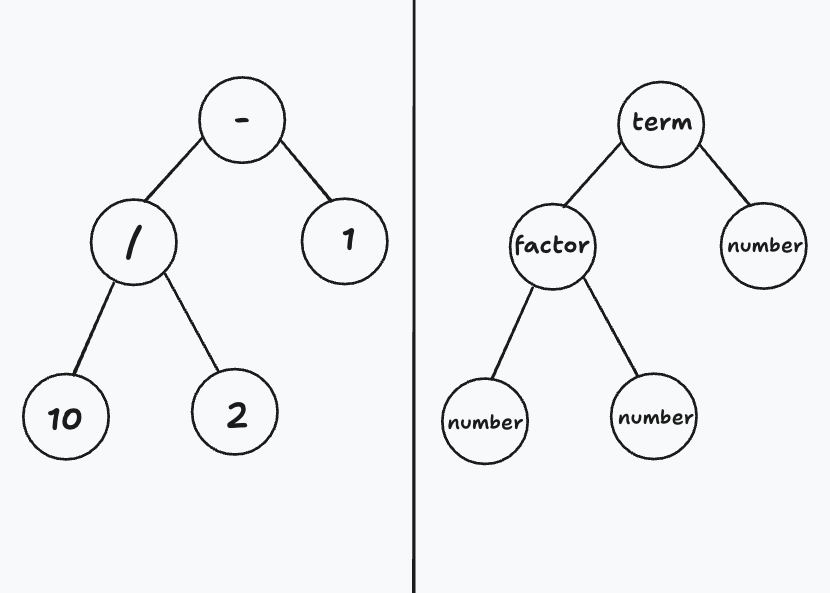

What we just did is essentially parsing, and is the process, by which we analyze and make sense of a language. In this case “making sense” means essentially figuring out which sequence of rules can bring us to this particular sequence of tokens. One problem with the grammar above is that is pretty ambiguous. For example 10 / 2 - 1 could have been generated in two different ways - one that yields 4 and the one that computes to 10. That’s because our small expression grammar is missing it’s order of operations. Also, remember that can of worms with associativity and precedence? We need to open it before it spoils and stinks up the place!

Below you can see a much more complicated grammar, that covers all bases, makes sure every possible arithmetical expression is unambiguously parsed.

expression → term;

term → factor ( ( "-" | "+" ) factor )* ;

factor → unary ( ( "/" | "*" ) unary )* ;

unary → ( "-" ) unary | primary ;

primary → number | "(" expression ")" ;

Abstract Trees

After performing the parsing operation on the code we start to kind of know what it does. That understanding takes the form of a tree. The tree structure produced by the parsing operation is usually called an Expression Tree or an Abstract Syntax Tree (if you want to be fancy) and represents structure of the code as defined by your grammar. Looking at the tree, that represents the example from above, we can see, that each element essentially represents an element of the grammar.

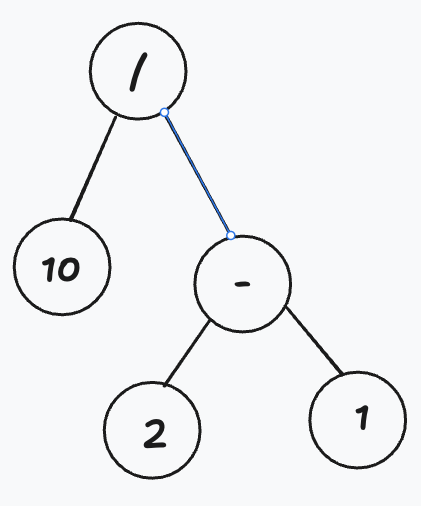

These kind of trees are usually called abstract because they omit some elements of the code. For instance - any parenthesis will actually be present in among the nodes of the tree, but would actually be encoded within it’s structure. This means, that the tree for 10 / (2 - 1) would look like this:

Another important thing, that parsing accomplishes is testing for correctness. If your parser fails to identify a production rule, that fits the given code it must throw/or return an error, that informs the author of the code what exactly is wrong with their code and how they can fix it.

Error reporting is actually a whole thing in language design and apparently consumes a lot of energy from the designers and implementors.

A Matter Of Interpretation

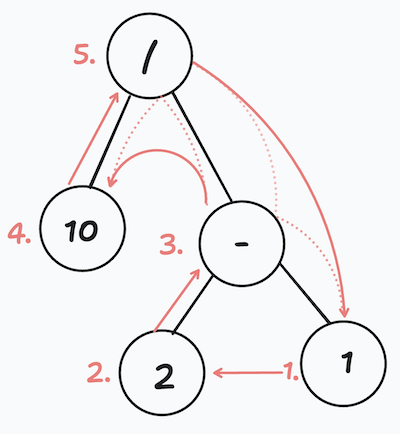

Now that we have our syntax tree, what do we do with it? The cool thing about trees (depending on your definition of cool) is that they can be traversed in different ways. Traversal not only lets you access the nodes of a tree in a certain order, but also allows you to do things with the nodes themselves. In order to interpret our code we need to do a post-order traversal of our expression tree - for each node we will firstly move down to traverse its children and then go back up and process the node itself.

In the tree above, you’ll notice that each binary operation has exactly two children. As we process the children of each node, the results of that processing become arguments for the processing of the node itself. In this case processing means executing the operation, that the node contains. For literals such as numbers it’s returning the number itself. So, interpreting a tree like this would look something like

- Return 1

- Return 2

- Execute 2 - 1

- Return 10

- Execute 10 / 1

In pseudocode it would look something like:

class Node

{

....

fun process()

{

foreach child in children

arguments.add(child.process())

return operation.execute(arguments)

}

}

Obviously, these steps will get you a very rudimentary interpreter, that can mostly perform arithmetic operations. However, they are the building blocks of any language. In a subsequent post I will go over the process in practice and give examples from my implementation of the Lox interpreter.